We Spot a Herd of Broncos Up on the Big Hill at the Carlisle Ford Nationals

By Joe Deladvitch

Tasty Fords On the Menu at Private Club’s Unique Car Show & Dinner Event

By Mark Storm

Podcast Recording Session Inspires Jerry Poston to Share His Mustang Story

By Jerry Poston

Mustang Owner’s Museum Visit Uncovers Plenty of Unexpected Discoveries

By Joe Deladvitch

SAAC’s Motor City Region Club Marks 50th Year with Show & Go at Ford’s WHQ

By Bill Cook

Mustangs, and Heavy Rain Make for an Unforgettable Carlisle Ford Nationals

By Joe Deladvitch

Ford Performance Returns to Pikes Peak with Electric Super Mustang Mach-E Demonstrator

By Ford Performance Staff

Chelsea DeNofa, Cameron McLeod, and Alex Bachoura Victorious at Le Mans Invitational

By Ford Performance Staff

Ford Announces Key Building Blocks of 2027 WEC Hypercar Program

By Ford Performance Staff

Junemageddon: Mustang Tackles Four Major Endurance Races in June

By: Alex Allmandinger, Ford Performance global sports car manager

7.3L Godzilla Swap Turns Dick Townsend’s 1999 Lightning into a Monster

By Richard Townsend Jr.

Collector’s Dream of Fine Fords Cross the Block at Big Annual Indy Auction

By Bill Cook

Scant Sun for Mustangers as Sprinkles Make Return to Great Lakes Stampede

By John M. Clor

Mustangs and Fords Still the Primary Power Behind Big American Muscle Show at Maple Grove Raceway

By Joe Deladvitch

Late-Model Award for 2015 Fusion Proves You Don’t Need a Classic Ride to Be Appreciated at a Car Show

By Rick Mitchell

Too Cool School: Students in RC Car STEM Program Sponsored by Brand X Opt for Mustang-bodied Racers

By John M. Clor

Annual FE Race & Reunion Honors Legendary Ford V8’s with Spectacular Classics Packing a Powerful Punch

By Bill Cook

Looking for the Biggest Blue Oval Extravaganza? Don’t Miss the Carlisle Ford Nationals June 6-8

By John M. Clor

A Father Brings His Son to a Club Meeting, So We Give Him a Prize & Get a Cool Ford Story in Return

By Ronald Tallman

Some Florida Cruise-In’s Are So Filled with Classic Collectible Fords, They Deserve a Longer Look

By Jeff Burgy

Exclusive: Q&A with Author of New Mustang Children’s Book Reveals Bid to Grow the Next-Gen of Ford Fans

By Ford Performance Staff

Joe Davis Creates an Indy Racer Inspired and Era Authentic 1922 Model T ‘Torpedo Tail Speedster’

By Matt Stone

When the Sun Comes Out So Do the Fords as Cars and Coffee Action Heats Up in Suburban Detroit

By Bill Cook

AACA Features 70 Years of T-Birds (& Fine Fords) during Show at American Muscle Car Museum in FL

By Jeff Burgy

Get Ready to Take Flight and Celebrate an Icon for Thunderbird Appreciation Day on Sunday, May 18th

By John M. Clor

T-Birds Rule the Roost in The Villages, Florida, at Monthly Car Show Held at Spanish Springs Square

By Jeff Burgy

Ford Offers Fans a Look at its Past, Present & Future During a ‘Cars & Concepts’ Event at WHQ in Dearborn

By John Clor

For Drew and Robin Hayes, Daughter & Granddaughter Find Meaning by Driving Warriors In Pink Mustangs

By Drew & Robin Hayes

Sprinkles Can’t Dampen the Party Vibe at Club’s Annual National Mustang Day Gathering in Dearborn

By John M. Clor

Mustang Clubs All Across Europe Unite with an Event and Launch of Long-Sought Pan-European Association

By Fabrizio Schenardi

Fandom Finds A Home: The Early Ford V8 Foundation Museum – A Place Where Flatheads Are Forever

By John F. Katz

During Annual Club Summit, Two Gen-Z Owners Pitch a Rethink for Events, Social in Bid for Younger Members

By John M. Clor

Owner’s Museum Draws Top Speakers, Cars, Events and Hall of Fame Inductees for National Mustang Day

By Gerard Ferraioli

Winning a Trophy at a Car Show is More Memorable When It’s at an Event That Pays Tribute to Veterans

By Rick Mitchell

Save the Date for October 24-25 and Join the Fun During Raptor Rally 2.0 at Lake Havasu, Arizona

By John M. Clor

After Nationwide Search, Rick Mitchell Rekindles Fondness for the Fusion with a Sweet, Blue 2015

By Rick Mitchell

Popular Annual ‘Ponies In The Smokies’ Event Proves a Perfect Jump Start for the Mustang Show Season

By John M. Clor

Pioneer Ford Car Designer Emeline King Dazzles the Crowd on National Mustang Day at Halderman Museum

By John M. Clor

After a Show Appearance, the Ed Martin Thunderbolt Winds Up Reunited with a New (Old) Owner Family

By Bill Cook

33 Ford GT’s Make Waves at 21st Annual Cars on 5th Show Featuring Luxury Exotics in Naples, FL

By Jeff Burgy

We’ll Give You One Last Chance to Check Out Some of Our Favorite Fords at the 2025 Detroit Autorama

By Joe Deladvitch

It’s Easy to Find the Best Way for You to Celebrate National Mustang Day (or Weekend) – Join the Club!

By John M. Clor

Media Gets a Sneak Peek at Saved Concept Cars and Project Vehicles in Newly Formed Ford Heritage Fleet

By Marcus Cervantes

Rainy Drive to a Car Show Makes for a Mega-Effort Cleanup that Brings Out the Sun – and an Award

By Rick Mitchell

UK Focus RS Club Member Chris ‘Kit’ Taylor Reveals How His Focus RS and its Community ‘Saved His Life’

By Chris 'Kit' Taylor

Got Cabin Fever? Check Out Nostalgic Displays of Station Wagons and Muscle Cars at the Gilmore Car Museum

Photos by Bill Cook

Mustang, Bronco and Trucks Make for Dominant Displays in a Strong Ford Footprint at the Chicago Auto Show

By Ryan Pasch

Autorama Extreme’s Cool Motoring Subculture Makes for Eclectic Mix of Rides that Transcends Generations

By Bill Cook

With the Chance to See So Many Iconic Fords, the Annual Iola Old Car Show Never Gets Old

By Dave Glickman

Surprise Ride in a Model T Makes Return to a Show for 2nd Year in a Row Better Than Winning a Trophy

By Rick Mitchell

Blue Oval Fans Find Fords of Every Flavor, from Hot Rides to Cool Classics, at Detroit’s 72nd Autorama

Photos by Bill Cook

Got Cabin Fever? Check Out Nostalgic Displays of Station Wagons and Muscle Cars at the Gilmore Car Museum

Photos by Bill Cook

March 24th to 29th Marks Kick-Off of the Mustang Car Show Season with ‘Ponies in the Smokies’

By John M. Clor

At 18, Star Drag Racer Jordan DaCosta Builds a Coyote Foxbody Plus Youth Interest in Racing

By Jordan DeCosta

You Might Be Surprised at Who Brings Classics to the Lake Street Cruise-In in South Lyon, Michigan

Photos by Mark Storm

Ready to Rock? We Take You Behind the Scenes for an Inside Look at the RTR Lab near Charlotte

Volunteering to Assist with Judging Adds to the Fun at National Capital Region Mustang Club Show

By Rick Mitchell

Cool Fords Spend Time in the Sun at Florida’s 25th Lake Mirror Classic Concours and Car Show

Photos by Eric Pasteiner

The Mustang World Loses an Icon with the Passing of Hal Sperlich at Age 95, Ford’s Pony Car Champion

By Paul Kampe

Enthusiasts Make Their Own ‘Spec Commercial’ Video for Reveal on March 9th to Honor 60 Years of Mustang

By John M. Clor

Ford Performance Hosts a 25 Season Launch Party to Help Get Fans Fired Up for More Racing Successes

By Joe Deladvitch

Let Some Hot Cars & Coffee Action in Suburban Detroit from Late Last Summer Take the Chill Off Winter

Photos By Bill Cook

Young Enthusiasts Bring Culture Shift to Detroit Auto Show with Special ‘Modded Detroit’ Display

By Austin Atwood

Dark Horse #3 Raffle Car Helps Cruise for a Cause Fight Cancer with its 14th Annual ‘Fall Ford Fest’

By Robert Kennedy

Ford Fan Finds Blue Oval Rides Galore at Hometown Rochester Heritage Rod & Custom Car Festival

Photos by Bill Cook

After Bad Weather Kept Forcing Rescheduling, 4th Time’s the Charm for East Coast Drifters Show

By Rick Mitchell

Hall-of-Fame Funk Musician Bootsy Collins and Wife Patti Drive Off with Presidential Awards in Their 02 Mustang

By Tina Scheafer & Bill Montgomery

We Uncover Ford Employee’s 4-year Resto Quest on a ’69 GT500 to Snag an Award at the ’24 Detroit Autorama

By Susan Lock

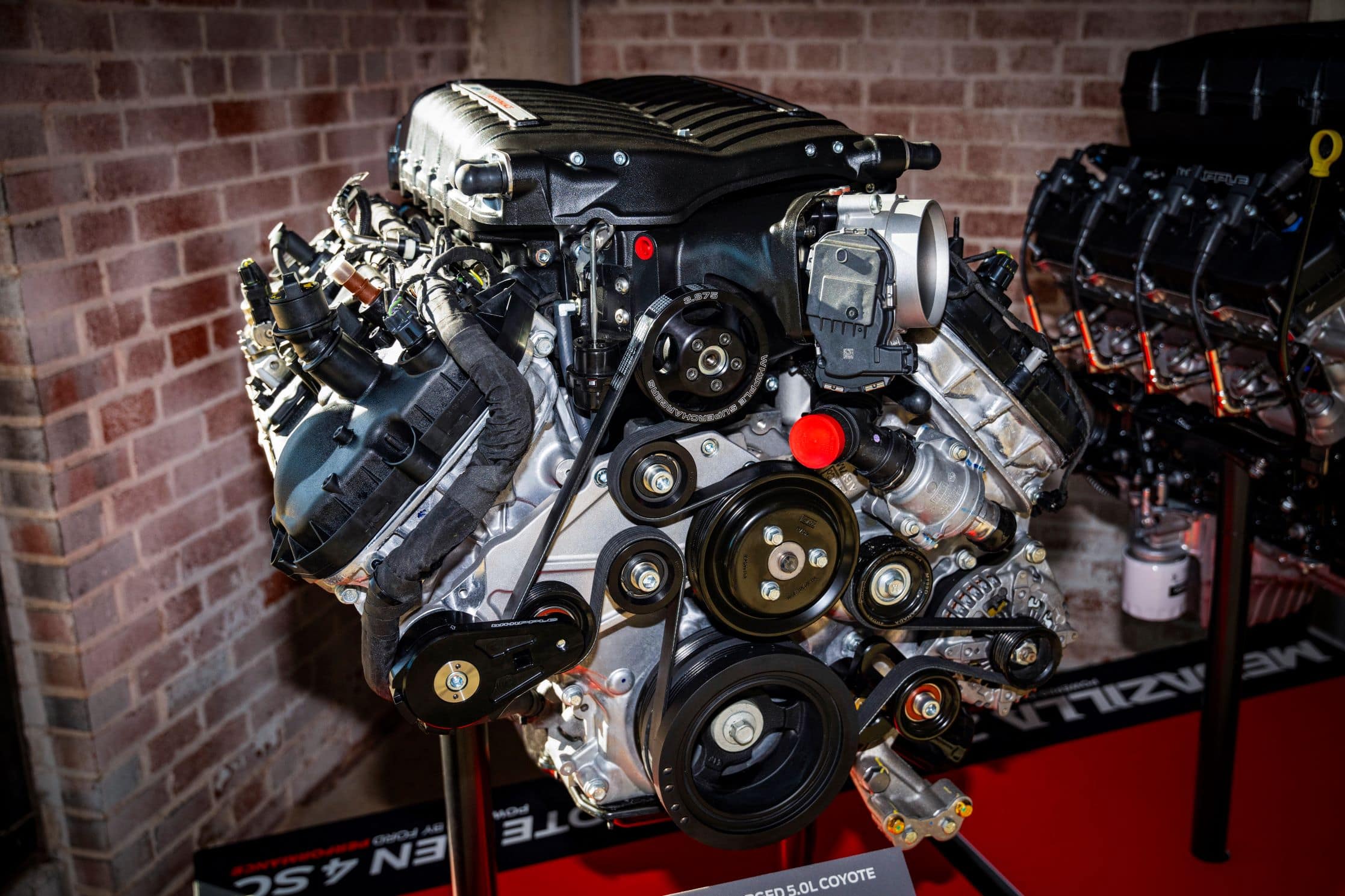

New Megazilla, Coyote Crate Engines Deliver More On- and Off-Road Power

By Kim Mathers

Come Explore the All-New FordPerformance.com Site to See How We’re Driving Ford Enthusiast Passion!

By John M. Clor

Ford Performance Celebrates Podium Finish and Thrilling Moments at the 2025 Dakar Rally

You Say it’s –4 and a Cold Wind’s Got You Down? Let Some 4H Camp Car Show Coverage Warm Your Soul

By Rick Mitchell

Ford Heats Up Reimagined Detroit Auto Show with RTR EcoBoost Mustang and GTD ‘Spirit of America’

By Austin Atwood

‘Santa’ Comes Through at the Last Minute to Land One Little Granddaughter Her Very Own Mustang

Submitted By Dave Olechovsky

Three Nominees from Two Ohio Clubs Inducted Into Halderman Museum Mustang Club Member Hall of Fame

By John M. Clor

Let This Car Show Called ‘Bumpers, Bikes & Bands’ Help You Forget About the Cold, Snow and Sleet

Photos By Mark Storm

What a Year! Take a Look at the Top 10 Enthusiast Stories from 2024 Posted on FordPerformance.com

By John M. Clor

Warm Up with this Visit to a Ford-Filled Midsummer ‘Cars & Coffee’ Gathering at Michigan’s M1 Concourse

Photos By Bill Cook

Beyond Sales and Service, Dealers Like Butman Ford Celebrate Ford Ownership with an Annual Car Show

Photos By Mark Storm

Subscribe to

Our Newsletter

Get up-to-date news, views, and races, including our weekly Fast News newsletter from Ford Performance.