Today’s Ford Performance and Ford Racing enthusiasts should consider themselves a bit spoiled (or a lot lucky) to be surrounded by 600-plus horsepower Ford GTs, Thundering NASCAR stockers, and several current-gen Mustangs that deliver true race car performance for the street (and victories at the race track). Yet the most foundational notions of Ford Performance and Ford Racing now go back a century, and sprang from the barest beginnings.

Think about it; the Ford Model T’s 177-cubic-inch inline four was rated at 20-22 horsepower. This of course was a valves-in-block, “flathead” engine running a one-barrel carburetor, and a single exhaust; the cylinder head did not even boast crossflow, meaning that the intake manifold and the exhaust manifold were both on the same side of the engine – not exactly the best scenario for heat conduction efficiency. Revs? The old hand-cranked Model T motor had no official redline, but most experts agree not to spin them beyond 2000-2200 rpm.

Excited yet? Oh well, what’s a racer or early hot rodder to do? Backed by its 2-speed planetary “semi-automatic” transmission (which offered three foot pedals – one for the brake, another to select between low and high gear, and a third one to engage reverse), figure a stock open-topped roadster-bodied Model T was good for 45-50 mph. Remember that the performance aftermarket wasn’t the global, high-tech phenom anything like the worldwide industry that it is today, so it was racing to the rescue. Of course, racers stripped their cars of anything that added unnecessary weight, and a variety of cottage-industry entrepreneurs, like Rajo, Z, Winfield, and others began developing high-performance camshafts, pistons, cylinder heads and exhaust systems to crank the little motor up and well beyond those measly 20 ponies. Google and FordPerformance.com? No such things.

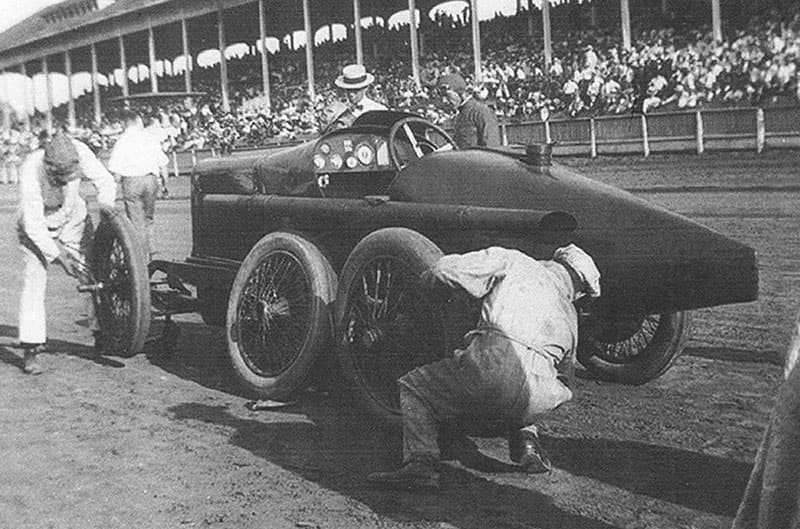

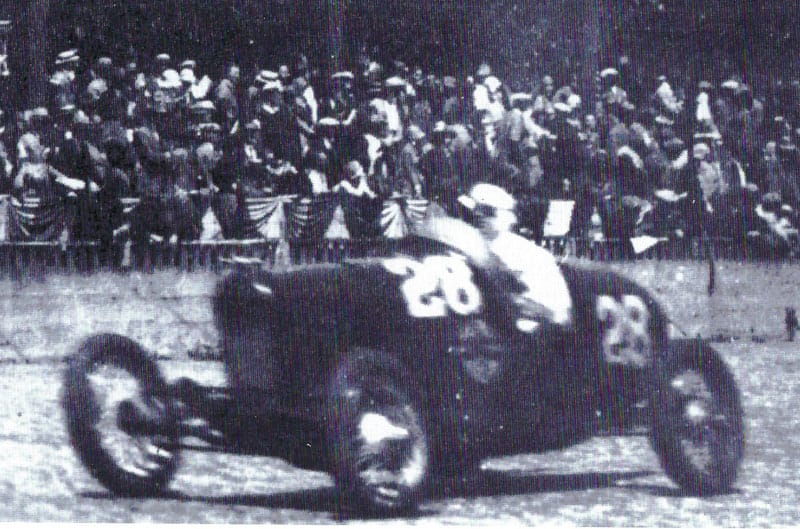

Model Ts and Model T-powered cars competed in all manner of racing programs and series. And besides circle track racing, Midgets and the forebears of Sprint car racing, hillclimbs, board tracks, jalopies and demolition derbies, a surprising number of Model T based and powered cars found their way to the famous bricks of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. Back in those days, the Indy 500 was dominated by luxury car-based racers from the likes of Marmon, Lozier, Stutz, Duesenberg, Studebaker and others, plus rare air exotica such as the highly engineered Millers, and anything running a howling DOHC Offenhauser straight four. Remember that in the 1920s and very early 30s, a used-up Model T was a $5 junkyard dog. So in proper racer (and what would become hot-rodder) style, those old Ford chassis were redesigned and repurposed into frames for racing, dressed in home- (or hand-) built bodywork that was lighter than a road car’s, and theoretically more (or not) aerodynamic too.

Ditto with the engines: Early aftermarket pioneers developed “speedway” products intended to beef up the Ford “banger’s” reliability and power output, with heads, carbs, pistons, exhaust, all what would become the usual hot-rod stuff. To what result? Maybe 50 horsepower.

No Model T racer or engine ever won the Indianapolis 500, but many qualified and ran (and sometimes well). These cars were nicknamed Speedsters and served as inspiration for the brilliantly blue and red “torpedo tailed” racer/roadster you see here. One particularly interesting run by a Model T based and powered entry came in the 1924 Indy 500. A young British driver named Alfred Moss drove to a solid 16th place finish ahead of Ford teammate Fred Harder in 17th. After returning to England, post dental school in the U.S., he married and had a son, whom he named Stirling. Yes, that Sir Stirling Moss, considered among the greatest-ever of British racing drivers, having won 16 Formula One races, an even-dozen World Sports Car championship events, finishing twice overall at the 24 Hours of Le Mans, and a record-setting win for Mercedes-Benz in the 1955 Mille Miglia open road race. Cars such as Moss senior and Harders proved inspiration for the brilliant blue-and-red Model T racer you see here.

Joe Davis, a now retired mechanical engineer and automotive restoration shop owner from Southern California (now transplanted to Southern Oregon) seemed destined to be a Ford guy from his earliest days behind the wheel of an automobile, as his first car was a decidedly forlorn $100 Model A. He and a friend later ended up with an abandoned Model T track racer, which they restored and converted to street use.

It was many years and cars later that Davis decided he wanted to build a new, street-legal car based on the shape, hardware and spirit of those great Speedsters of back in the day. He recalls being particularly inspired by the above-noted Alfred Moss’s Model T-based Indy racer from 1924, and cars just like it. “Further inspiration was fueled by a race I had heard about in Cincinnati in 1916,” he said. “I read a great article about it: https://queencityhistory.substack.com/p/when-indy-came-to-cincy. I also read an article about Stirling Moss and his father which was another inspiration.”

Davis settled on the year 1922 to set the benchmark for the style and hardware used for this utterly unique build. “I designed the car using many photos of race cars of the day,” he explained. “There is one really good book, ‘Indy Cars 1922-1939,’ by Karl Ludvigsen. Lots of photos and some good stories. A large photo of the 1916 Cincinnati race was another. Don Azevedo did much of the chassis work and was very knowledgeable, as his father built eight speedsters back in the 1950’s and 60’s and had information about the race cars from the 20’s. His two sons, Don and Larry, worked by his side and are both enthusiasts today. At the time this was built I had retired from my day job as a mechanical engineer in Silicon Valley and started a restoration business for Pre-War cars only. My wife and I owned a piece of land in the Santa Cruz mountains, and I built a shop which started out at 1,000 square feet and in the next 5 years expanded to 3,000 square feet. We had our own paint shop and equipment to do metal shaping, so building the body was easy.”

Not obvious in the photos is the rear section and “tail.” “It has a metal frame inside with wooden stringers and is covered by an aircraft-grade [canvas type] fabric, then painted,” Davis noted. “This was not uncommon in the day, as it saved weight and made fabrication easier. Bentley race cars of the late 20’s [and many small aircraft] used fabric-covered bodies with great success.” The robust fabric made great sense as it is relatively light in weight compared to metal panels, is available, and easy to form around a framework structure of wood and metal stringers.

Another engaging aspect of the build was hunting down all the period bits and pieces to finish the car and keep it early-1920s authentic. “The chassis was finished in 2008, the body completed in 2010, so it took a few years to bring everything together,” Davis said. “The chassis was found in the woods up near Lassen.” You’ll notice the body has no doors, only cutdowns in the side panels allowing access to the passenger compartment. Getting into the car is much like boarding a horse. You’ll also notice stirrups on either side of the car; put one foot on the stirrup, then hoist your other leg and torso up and over, into the “semi-bucketed” seat.

The engine was carefully spec’d and built from the oil pan up (no such thing as a crate motor for a ‘20s era Ford engine). “The stock Model T engine ran a very low compression ratio due to the poor quality of the gasoline, about 50 octane in the 1920s,” Davis said. “The aircraft industry forced the oil companies to make higher octane, allowing for higher compression ratios. This engine was rebuilt using aluminum pistons, stainless-steel valves and a high-performance cam. It has an 8:1 aluminum head and we built a custom intake manifold and header. The carburetor is a Winfield updraft size ‘AA,’ which was a very commonly used carburetor on the racing circuit. The custom camshaft was ground using one of Ed Winfield’s profiles.” The result? About 50 horsepower at 2,000 rpm. Yes, you read that correctly – 50 horses, at a not-so-screaming 2,000 revs.

Don’t expect a high-tech paddle-shifter transmission or even something as exotic as a Tremec 6-speed. “The Model T transmission and engine are one unit and cannot easily be separated,” Davis explained, “so as was common in the day, we added a Warford Transmission, right behind the T engine and transmission. This offers an overdrive, underdrive and straight-through [direct drive]. The original Warford had [non synchro] straight-cut gears and was difficult to shift. A company in Kansas City has been making an improved knockoff for 25 years. It has a system similar to synchromesh, but slightly different, but very easy to shift and quiet. We also run a Ruckstell two-speed rear axle which is an underdrive or straight-through [direct drive]. We put a high-speed gear ratio in the rear end, so we can go very fast, but have lots of gears for climbing.” Much like a modern big-diesel semi, this combination allows for 12 forward speeds, although it requires a lot of shifting to use them all in sequence.

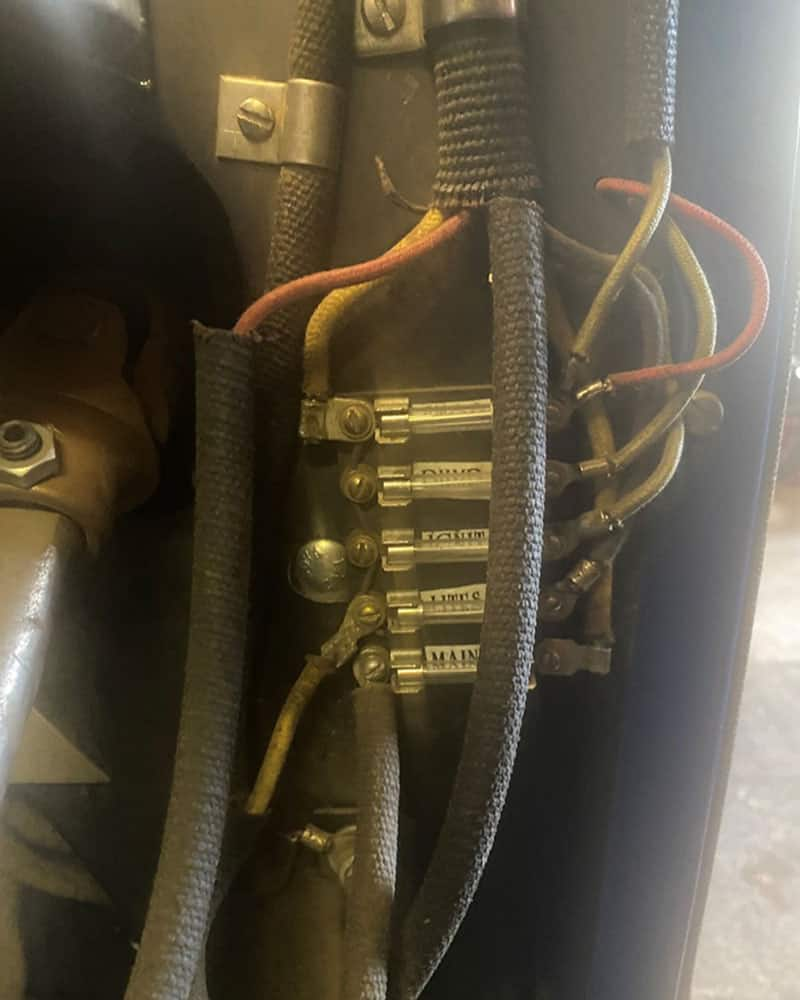

The cabin offers an interesting combination of accoutrements. The driver gets minimal wind and bug protection via a cutdown adjustable single-screen cowl mounted dead ahead of the massive wood-rimmed streeting wheel, while the passenger/riding mechanic gets goggles and a scarf. The two stalks on the steering column are neither turn signals nor windshield wipers; one controls “spark” or engine timing, the other is the throttle. Only three gauges are needed to keep track of the car’s speed and the chortling I-4 engine. A “MotoMeter” radiator cap also serves as the temp gauge.

You’ll note that the grille and radiator don’t at all resemble that of a Model T; they were sourced from a Whippet, perhaps slightly taller, and larger than those of the squarish Ford grille shell and rad. It was common on custom/home built-racers of the day to use what they felt were best available, no matter the maker – like Studebaker brakes, so-and-such differential, and so on. Davis worked hard to source and install only early 1920s hardware when and where possible, thus it is historical society certified and registered as a 1922 Ford. He’s never tracked the car, but drives it often and actively, having participated in at least a dozen “old timer” road rally runs; many averaging at least 200 miles – with some more than 500, and one at 650. He says the 1,200-or-so-pound machine is easy and fun to drive, and handles nicely, although crank it up to about 50 mph and “you really feel like you’re flying.”

Alfred Moss would be pleased. And so would Henry Ford.

FORD PERFORMANCE PHOTOS / COURTESY JOE DAVIS COLLECTION, KIRK GERBRACHT & ED ISKENDERIAN